Introduction

Proper programming is important to make good progress in Powerlifting. A well written training program will help you to continue to make gains in the long term with minimal disruption from injury. That being said, particularly for beginners, you don’t need the most perfect program in the world to make progress, so try not to get so worried about it to the point that it actually hinders you. A simple, basic template program will probably do. You only really need an expertly crafted, individualised program when you get to a really high level. The distinctions I’m going to make on this page are really just to separate what makes an “optimal” program, from simply a good program.

There’s a disclaimer I should mention here before I begin. The only thing I’d really warn you away from is the potential allure of really intense programs like the Smolov Squat program or Bulgarian Method style training. These programs get you lifting at really high intensities, possibly for high volumes, at a really high frequency (every day or even twice a day for the Bulgarian method). You may hear stories about people making incredibly rapid progress on programs like these… initially. What normally happens is they pretty soon burn out and/or get injured. Keep in mind that programs like these were designed to essentially weed out the lifters who couldn’t handle it, and were for lifters who were on all kinds of performance enhancing drugs that you’re (probably) not on.

It pains me to say this because us Powerlifters despise long distance running, but Powerlifting really is a marathon, not a race. There’s honestly no rush to get as strong as you can, as fast as you can. People who try that often don’t last long. The best lifters are the ones who make consistent, slow, steady progress over the long term and stay injury free. So if in doubt, go for a more sensible, easier program.

If you’re still not convinced, think about it this way - say you managed to make 2.5kg of progress on each of your lifts not every week, but every month. Doesn’t sound like a lot does it? But now consider that if you could keep that up, you’d put 30kg on each of your lifts in a year - thats 90kg on your total! That’s a huge amount of progress! Now consider that unlike many sports, most people in Powerlifting can carry on making progress until they’re mid 30s or even in their 40s. If you kept up that rate of progress, you could be lifting more than Ray Williams before you leave the sport. Why isn’t everyone squatting 500kg then? Because in reality, it’s keeping that progress consistent that’s the hard part.

Recommended Programs

If you’re just looking for some quick recommendations for Cookie Cutter Programs, I won’t beat around the bush. Other free options, as well as handy spreadsheets of many well known programs can be found on LiftVault. Some great programs we’d recommend are:

- Jonny Candito’s Programs - Especially the Beginner and Intermediate programs. Find them here. The Intermediate one comes with a convenient table but the Beginner one doesn’t so we’ve made a convenient excel version you can download here. There’s a lot of other really good information on the full pdf on his website though so don’t just use this as a replacement for that! Give that a read too, but then you can use this template to record your training. These programs have you training 4 days a week.

- RTS Generalised Intermediate Program - This is a great program, written by arguably one of the best coaches around at the moment, Mike Tuchscherer. Find it here. Keep in mind though that it’s only designed for strength/peaking for a competition, and it is quite intense depending on how you use it, so I wouldn’t recommend re-running it again and again. It’s also given in a really annoying format, so there’s an excel version you can download here. This program has you training 4 days a week.

- TSA Programs - Over at The Strength Athlete, they have a whole host of useful free resources, including 3 programs. They have a beginner program and 2 intermediate programs. Click on “TSA programs” to head over to their website. They uses RPE like the RTS program but also percentages. They tend to favour specificity so you’ll be doing competition style squats, bench presses and deadlifts a lot, but they do also have some flexibility to them. They often have you working with a fair amount of volume but at very manageable intensities. These programs are GREAT in my opinion because they also incorporate longer term intelligent periodisation, deloads, peaking and tonnes of advice and information on how to use them. They are adjustable so you can either use them to peak for a competition or just as a training cycle to repeat. They all have you training 4 days a week.

- Calgary Barbell Programs - The folks over at Calgary Barbell have both a 8 and 16 week program. Find the spreadsheets here. These are structured fairly similarly to the above TSA programs, having you training four days a week, with a squat frequency of 3 times, bench 4 times, and deadlift 3 times weekly. Again, a fairly high specifity. If you can brave it, I’d probably recommend the 16 week program over the 8: the longer timeframe permits decent length hypertrophy, strength, and peaking blocks, letting you run it into a meet or repeatedly as a training cycle. Saying that though, I personally failed to complete the full 16 weeks each time I tried due to lockdown…

- The Texas Method - Used by Mark Rippetoe over at Starting Strength, the Texas method is beautiful in its simplicity. Find the original here. It only has you training 3 days a week and is just a week template you run over and over again, so it’s great for those with a busy schedule. It consists of a volume day, where you do 5x5 work outs, a lower volume, recovery day, and an intensity day where you work up a PR set of 5. It is perfect for beginners up to late intermediate lifters, but might stop working as well when you get to advanced lifters as they simply can’t progress week to week like beginners can. However, the original program is designed for general strength, rather than specifically for Powerlifting, and has you doing Power cleans and benching to overhead pressing in a 1:1 ratio, both of which are pretty unnecessary for Powerlifting. So I’ve also given a slightly altered ‘Powerlifting version’ of the Texas method. Download here.

I’d also like to direct you towards a really useful review series by PowerliftingToWin on YouTube. The first episode is shown below, but do go and watch the rest. He goes over the basic programming principles and uses them to review a number of the free, cookie cutter programs out there on the internet at the moment.

I’ll also recommend to you a really useful tool on the Reactive Training Systems (RTS) website - their training log for recording and monitoring your training. This is great if you’re the sort of person that likes to be analytical about their training, but does take a bit of effort to keep up to date with. Go to the RTS website and go to the “apps” section. You need to create an account but it’s totally free. The great thing about it is that based on your RPE ratings (see what these are below) and how they change over time, it constantly monitors your fatigue rating. It also creates real time estimates of your 1RMs and your Wilks score based on your body-weight and your rep work.

The Principles Behind Programming

If you want to learn more about the logic behind programming and why a good program is good, so that you can program for yourself or make intelligent tweaks to individualise programs to yourself then keep on reading.

The best resource I’ve found to explain the factors that go into constructing a good program is the Scientific Principles of Strength Training series by Juggernaut Training Systems. Again, the first episode is embedded below but do go and watch the whole series. They describe the 7 most important programming variables, in order of importance:

- Specificity

- Overload

- Fatigue Management

- Stimulus, Recovery, Adaptation (SRA) cycles

- Variation

- Phase Potentiation

- Individual Differences

You want to try to satisfy as many of the principles as possible, which can be a bit of a juggling act. The order of them is important - it means you can’t sacrifice a higher principle to achieve a lower principle e.g: variation is good, but not if you’re completely sacrificing specificity in the process.

So what do these principles mean? First, it might be worth defining some key terms:

- The Main lifts are the competition style Squat, Bench and Deadlift.

- This can normally vary but I define Variation exercises as some variation of one of these three movements, but where you’re still fundamentally doing a squatting, benching or deadlifting movement (e.g: pause squats, close grip bench press, pause deadlift etc).

- Accessory exercises on the other hand would include different movements (e.g: leg extensions, tricep extensions, pull ups etc), which can be used to target particular muscle groups.

- Volume: An expression of how much total weight you’ve lifted in kilos. Normally this is weight x reps x sets (tonnage), or it can be in sets/week

- Intensity: How heavy the weight on the bar is relative to your max. Normally this is expressed as a percentage e.g: 80% of your 1 Rep Max

- Frequency: How many times you train a lift per week. This would include the competition lift and its accessory exercises.

- Specificity: How similar an exercise is to the competition exercise

- Maximum Recoverable Volume (MRV): the maximum volume your body can recover from in a week, given in sets/week. If you exceed this for too long, you can end up over training

- Maximum Adaptable Volume (MAV): The hypothetical weekly volume at which you make the most progress, in sets/week

- Minimum Effective Volume (MEV): The minimum volume required to make some progress, in sets/week

- Periodisation: long-term cyclic structuring of training and practice to maximize performance to coincide with important competitions

- Phase Periodisation: Implementing periodisation by splitting training into phases or blocks where you focus on developing one particular physical quality in that block

- Microcycle: The smallest repeatable cycle of training. Normally a week.

- Mesocycle: A block of microcycles designed to develop a particular physical quality e.g: a hypertrophy block. Would normally last e.g: 6-8 weeks

- Macrocycle: A group of mesocycles which will incorperate all the mesocycles leading up to a competition. E.g: a hypertrophy block, strength block and peaking block together would make up a macrocycle. Often lasts 6 months - over a year

- Adaptive Resistance - the process by which, after a long time exposed to the same or a very similar stimulus, your body stops adapting to it as well - and your progress stalls

- Directed Adaptation - the process of directing your body to adapt to a particular stimulus (e.g: squatting triples) - which will cause you to have improvement in that area.

Specifity

Specificity refers to how similar an exercise is to the competition lift: a one rep maximum squat/bench/deadlift to a competition standard, with competition equipment. A more specific exercise is generally going to transfer better to the competition lift. This is the number one principle of training, because, to use an extreme example - you could write a perfect program satisfying all the other principles, but if it’s a long distance running program, it ain’t gonna get you a bigger 1RM squat, no matter how good at running you get.

Specificity is a spectrum, and this principle does not mean that doing anything but a squat is wrong, but it does mean that you will need to include competition-style squating, benching and deadlifting in your program. It also means that the rest of the training you do should be directed at improving those 3 lifts in some way. If you’re doing accessory work - make sure you’re targeting the muscles that are used in those 3 lifts. And keep in mind that you might get more bang for your buck doing pause squats, rather than leg press as an accessory exercise, as the former also gives you the chance to improve your technique and the strength you develop from it will be more specific to your squat.

Generally it’s a good idea to have overall specificity slightly lower further from a competition and increase as you move towards a competition. This is because far out from a competition reducing specificity will reduce staleness and risk of injury, helping to satisfy the principle of Variation (see below). Also, accessory exercises like leg extensions are also going to be easier to recover from than heavy squats, so they allow you to get more volume in which can be useful for hypertrophy. However, as you approach a competition, you’ll need to increase the frequency that you do the competitive movements/a variation of them, and decrease your accessory work a bit, so that you can develop the technical mastery required for the competition.

Overload

The Principle of overload essentially means that training needs to be hard enough, and needs to get harder over time. This is the number 2 principle because no matter how much you lift, if you never add any more weight to the bar, you’ll never get stronger.

Ideally you want to spend most of your time training close to what’s termed your maximum adaptable volume (MAV), and below your Maximum Recoverable Volume (MRV). These volumes will vary from lifter to lifter so it can take some experimentation with different programs and different volumes to see which you make the best progress at. You then want to try to slowly push that limit up by adding either weight to the bar, sets, or reps, not necessarily from session to session, but maybe from week to week and certainly from mesocycle to mesocycle. If you want a rough starting point, Juggernaut Training Systems have come out with a useful tool which I talk about on the ‘Finding your MRV & Frequency’ page.

Increasing volume will be best for making hypertrophy gains while increasing intensity will be best for making strength gains and for peaking for a competition.

The reality of this principle is that smart training is hard training. Not so hard that you’re failing sets all over the place and so sore you can’t walk, but it should be tough if you want to get stronger.

Fatigue Management

Unless you’re a beginner and you can make progress week to week consistently, training that’s hard enough to drive the best gains will also inevitably cause fatigue to slowly accumulate. If too much fatigue accumulates, your performance will drop. So this is the principle you need to balance with overload.

If you feel fine, your motivation is still high and you are able to hit your prescribed weights without failing, you’re probably fine and you can rest easy with the knowledge that your fatigue is still low enough that it’s not significantly hindering your performance. However, if you feel really beat up, your motivation is really low, and you find yourself missing weights that should be very manageable for you, you may have over reached a bit.

This doesn’t mean your program is bad, but it does mean you may have to dissipate the fatigue you’ve accumulated. This can be done with a deload week - where you train with low volumes and intensities. Try to avoid just not going to the gym at all as you’ll lose some of the technical prowess you’ve developed, and some light training can improve recovery. You may also want to look at some of your lifestyle factors outside of the gym. Are you getting enough sleep? Are you eating enough? Are you unusually stressed? All these things can affect your ability to recover from training.

Fatigue management is also particularly important while peaking. When you peak for competition you need to balance fitness and fatigue. Ideally, you want to rock up on competition day with the maximum fitness (strength and technical ability to complete the competition movement) and minimum fatigue. This is why you generally train in a very intense way with very heavy weights (but low volumes) while peaking (which wouldn’t normally be sustainable), then you taper and take a deload week before the comp. Getting this right is important as too much of a deload would make you feel detrained and weaker on the competition, while not deloading at all will mean you’re not recovered on competition day.

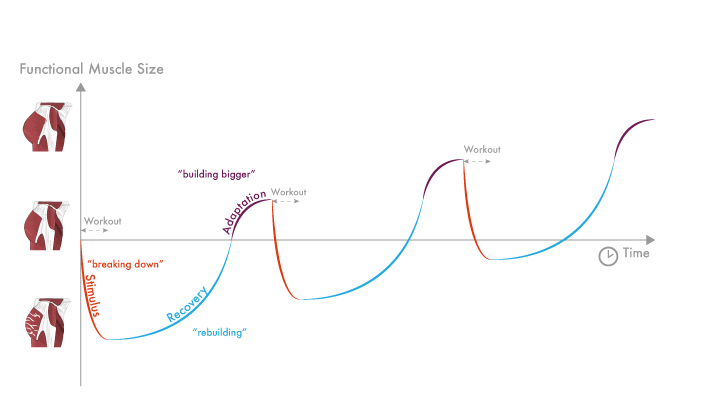

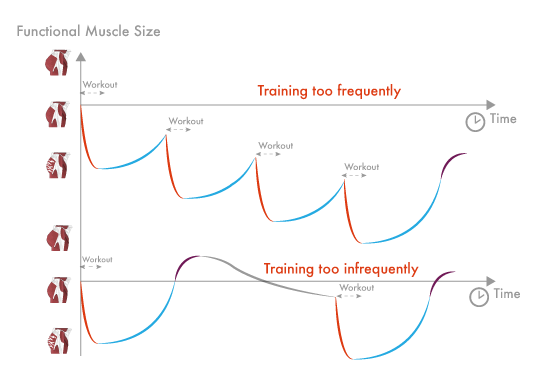

Stimulus, Recovery, Adaptation (SRA)

Stimulus, Recovery, Adaptation curves describe the process your body goes through after you lift: First, you lift (the stimulus), then your body is fatigued, so your performance (e.g: strength or functional muscle size) temporarily drops, then it recovers back to baseline, then your body adapts, increasing your performance above base line. If you leave it too long however, this adaptation will dissipate. How long this process takes is one of the things that determines optimal frequency of lifting. You can see that the best time to train again is at the top of the adaptation peak.

Different exercises with different weights will stress the muscles involved to differing extents. Deadlifting takes the longest to recover from as it generally uses the heaviest weights, so it has the longest SRA curve. This is why most programs only have you deadlifting once a week, maaayybe twice a week. Then come squats, then bench press, which have the shortest SRA curve out of the 3 main lifts and so can normally be trained the most frequently. This is why a lot of programs will have you squatting 2-3 times a week and benching 3-4 times a week. This doesn’t mean that these frequencies will be the same for everyone! There is no magic “how many times a week should I squat?” number. But rather, they’re the average. It can vary depending on gender, size, leverages, strength, experience, whether you pull sumo or conventional etc…try out some different frequencies for a few months at a time and see which work for you.

Another thing that complicates this somewhat is that different physical qualities also have different length SRA curves. Nervous System (NS) force production has a longer SRA curve than Hypertrophy, which has a longer SRA curve than technique. This is why you may want to vary the intensity during the week too. Luckily, squatting similar to your competition squat even with fairly light weights will help develop your technique, but only workouts with enough volume will generate hypertrophy, and only workouts with a high intensity will stress the Nervous System. So what can work is, say if you squat 3 times a week, having a Heavy, Moderate and Light day. That way you’re stressing the Nervous System once a week, Hypertrophy Systems twice a week, and working on your technique 3 times a week.

Also see the ‘Finding your MRV & Frequency’ page for a guideline of roughly where to start.

Variation

Some variation in your training (or “muscle confusion bruuhh”) can be useful in your training to prevent staleness and Adaptive resistance. Adaptive resistance refers to when you do a particular exercise with a particular set and rep scheme for so long, that your body starts to adapt to it less and less, and your strength gains plateau. This means that, unfortunately, even the best program won’t work forever. Not only that, but keeping training exactly the same for too long can increase the risk of overuse injuries and just get boring.

However, keep in mind that variation is only principle number 5. This is because if you had a program where you squat, bench and deadlift, with overloading weights, while managing your fatigue, and at a proper frequency, you’ll still make really good progress in the short term, even if there was no variation whatsoever. What a proper application of variation does NOT look like is totally changing the exercises you do from session to session, week to week. This will just mean you can never get good enough at any one exercise or set/rep scheme to make any meaningful progress in it. This would be a situation where you are not allowing yourself to achieve proper Directed adaptation. Balancing directed adaptation and adaptive resistance is the key to applying the principle of Variation correctly. Too much variation can also violate the principle of Specificity.

In order to achieve Directed adaptation you must expose your body to a set of exercises and rep ranges consistently for a long enough time. What you want to do is stick with a set of exercises for a few weeks or months until you start to see your gains plateau, then change it up a bit. This could just mean reducing the reps on all of them by a couple and upping the intensity. Or it could mean introducing some new exercise variations to target new weak points that have developed.

Different types of exercise can also run into Adaptive resistance after different periods of time. You want to make sure you’re practising the competition lifts for AT LEAST 8-16 weeks before you get to a competition. Beginners in particular may never take a complete break from doing the competition lifts, as they need even more practice at the competition lifts to build their technique. Meanwhile, you could probably rotate variations of the competition lifts every 4-8 weeks, and accessory exercises could be rotated roughly every 4 weeks.

When selecting which variations and accessory exercises to put into your program, you don’t want to just stick exercises in randomly just because “well I saw Larry Wheels doing it and he’s strong”. Larry Wheels will need to prioritise different aspects of his lifts to you. I’m also not entirely sure if he’s really a human being or some alien from a galactic race of muscle lords sent to crush us puny humans…

Ideally, you should be able to point to every aspect of your program and give a reason for why it is the way that it is. So you want to select your exercises so that they target your individual weaknesses. In order to help you with this, I’ve also written a short ‘Addressing Weak Points’ page that you can check out.

Phase Potentiation

Phase Potentiation essentially means splitting your training throughout the year into phases, where you use one phase to increase the effectiveness of the next phase. What this looks like in Powerlifting is starting far out from a competition, with a hypertrophy phase to build some more muscle, then progressing to a strength phase to make that muscle stronger, then progressing to a peaking phase, where we adapt our nervous system to handle really heavy weights and perfect our technique ready for a competition.

The analogy here is to imagine you’re building a skyscraper. Your hypertrophy represents the foundation your skyscraper rests upon. And you will have to dig down a bit to build this (meaning your strength may decrease temporarily while in a long hypertrophy phase), but that’s okay, because competitions don’t generally jump up on us by surprise. Your strength represents the floors of the skyscraper itself, building higher and higher to increase your 1RM, and your peaking represents the antenna on top of the skyscraper - a way to squeeze out some extra height right at the end, given the strength you’ve just built.

The principle of Phase Potentiation is another reason (in addition to variation) why you wouldn’t want to just train with maximum specificity (always doing heavy singles) all year round. This kind of training doesn’t have enough volume to build more muscle, and in the long term, you’re going to need to build more muscle to progress, especially as a beginner. Also, training a single modality at a time is likely going to be more effective than trying to increase hypertrophy, strength and neural qualities all at once, where the training for one will interfere with the others.

Your hypertrophy phase may last from 3 weeks all the way up to 6 months (but more commonly capped at about 3/4 months) depending on when your next competition is. It will involve low intensities of about 60-75% of your 1 rep max, for sets of 6-12 reps, and high volumes of 15-30 sets per week directed at each lift (squat/bench/deadlift).

The strength phase can last a similar amount of time to the hypertrophy phase, but will involve higher intensities of 75-90% (females & Beginners)/70-85% (Intermediate/advanced) of your 1 rep max, for sets of 3-6 reps, for lower volumes of 10-20 sets per week directed at each lift.

The peaking phase will only last about 3 weeks to at most 3 months (Less if you’re more beginner - more if you’re more advanced) and will involve the highest intensities of 90%+(females/beginners)/85%+ (Intermediate/advanced), for sets of 1-3 reps, for the lowest volumes of only 5-10 sets per week directed at each lift. The volume has to reduce because the intensity is so high that it gets harder to recover from the training you’re doing. It shouldn’t last too long because at volumes that low, you can end up dropping below your maintenance volume and losing some muscle size if the phase lasts for a long time.

Keep in mind that beginners should spend more of their time in the hypertrophy phase as they will likely need to build more muscle. I’m sorry, but if your knee is the widest part of your leg, you’re not going to squat 200+kg, no matter how many strength blocks you do. At the end of the day, it’s muscle that moves weight, and at some point, you’ll need to build some more to make more progress. Meanwhile, an advanced lifter may spend very little of their time in a hypertrophy phase, especially if their body-weight has maxed out their weight class, and most of their time in strength phases, with longer peaking phases.

Also here, see the ‘Finding your MRV & Frequency’ page for details of how to tailor these volume ranges to you.

Individual Differences

This last principle is essentially an asterisk to all the other principles. The specifics of how best to apply all the other principles will vary slightly depending on the individual. However, it’s the last principle because most cookie cutter programs designed for the average person will still work perfectly well for most people, unless you’re really advanced. Allowing for individual differences is the icing on the cake that takes your training from ‘very good’, to ‘absolutely optimal for you’. This can be why having a coach or some personalised programming can help as you get better and better.

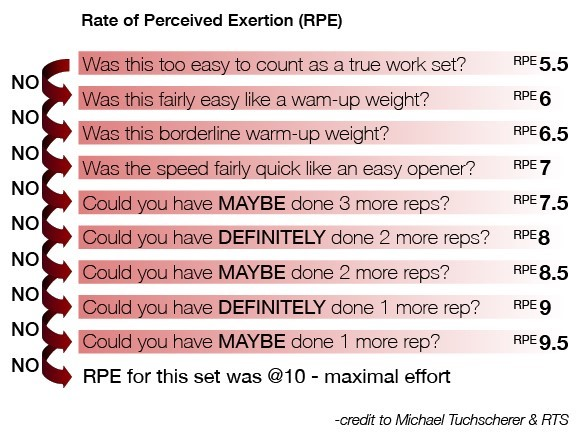

However, there are lots of schemes people have developed to try to create cookie cutter programs that still cater to individual differences to an extent. The best known of these is probably using RPEs. RPE stands for “Rate of Perceived Exertion”, and is actually used in a lot of sports. In Powerlifting, it refers to a 1-10 scale of difficulty, where RPE10 is maximal effort - either you failed, or you could not have done another rep. RPE9.5 means you could have maybe done another rep, RPE 9 means you definitely could have done another rep, RPE8 means you could have done two more reps and so on.

RPEs can then be used as feedback to tweak the number of sets you do or your weight progression. However, it’s a bit of a skill to be able to rate RPEs accurately that requires some practice to develop. For this reason it’s not necessarily best for beginners to jump straight into regulating their programs with RPE. Beginners also require the least individualisation to make progress.

Personally, I find RPE 7-8 to be the sweet spot for optimal gains.

Generally larger, taller lifters cannot tolerate as high volume/frequency. Stronger lifters also may train a lift less frequently as, because they are lifting more weight with each rep, their training stimulus is larger. That being said, work capacity can be built up over time to increase a lifter’s maximum recoverable volume (MRV) so sometimes these factors balance out in experienced lifters. Previous sport experience can also increase MRV as well as muscle fibre type.

Female lifters can and should train a lift more frequently and with more volume than male lifters. Beginners should generally train more frequently, but further from failure, as they need to focus on learning the technique of the movements. Beginners often also need to focus more time on hypertrophy to initially build the muscle to eventually lift bigger weights.

Also keep in mind that optimal training for you may change throughout your lifetime. This will change as you get stronger, increase your work capacity, your technique improves and you age. Lifestyle factors can also make a difference.

Learn a bit more about how these variables affect your optimal volume and frequency on the ‘Finding your MRV and Frequency’ page.

Tailoring your program to yourself can also involve addressing your weak points. If you squat very bent over, you may need to devote more time to training your back. If you find your upper back rounds in the squat and you can’t keep your chest up, add some pin squats to your program. If you want to work on your squat balance and technique, add some tempo squats. If you’re weak off the floor in the deadlift, add some pause deadlifts etc… - the specifics for this are given on the ‘Addressing Weak Points’ page.

One of the things this all means is that, when you’re watching high level athletes, they will and should train very differently to you. Try not to think about the training they’re currently doing, but rather what they did to get to where they are now.

Example

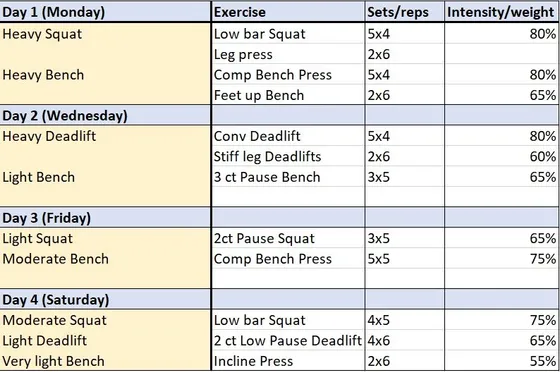

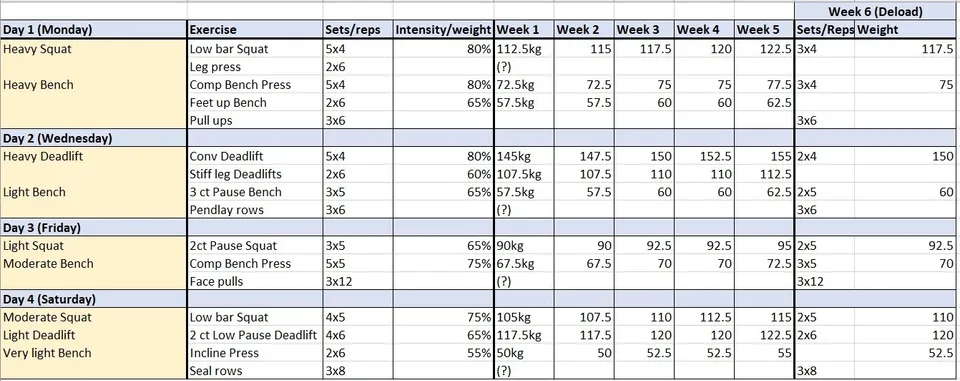

So now we have an overview of the basic principles of Programming, and you’ve worked out rough estimates for your MRV and optimal training Frequency on the ‘Finding your MRV & Frequency’ page, lets see what it all looks like when put into practice. We’ll have a go at making a basic program template for our friend from the MRV & Frequency page, Mr. Broseph McGainz. We’ll add to our description of him that he wants to design a strength block and he has a competition in 16 weeks. Also, he’s weak out of the hole in the squat, off the chest in the bench press and off the floor in the deadlift. He wants to train 4 times a week. He competes raw, squats low bar and deadlifts with a conventional stance.

We’ll start with his MRV ranges and frequencies. For him, his MRV estimate ranges were: 13-19 sets in the Squat, 15-23 sets in the Bench and 11-15 sets in the Deadlift. Remember that this is the MAXIMUM volume he can recover from, so his Maximum Adaptable Volume (MAV), is likely on the lower end of these ranges and that’s where we should start. Let’s say: 14 sets in the Squat, 17 sets in the Bench, and 11 sets in the Deadlift. His frequencies were 3 times a week squatting, 3-4 times a week benching, and 2 times a weak deadlifting.

Remember to undulate the difficulty of your sessions a bit. I’m spacing the sessions out through the week sensibly, particularly trying to make sure he has at least a day to recover a particular lift before a heavy session in that lift. Also notice how, to prevent intra-session fatigue interfering with the quality of his training, I’m trying to avoid putting, for example, heavy deadlifting and heavy squatting on the same day. The first stage is shown on the left below:

The next step is to add in the exercises, individualised to target Mr. McGainz’s weaknesses. For ideas of these exercises, see the ‘Addressing Weak Points’ page. You can see what I’ve entered in as an example above, on the right.

On the heavy, volume intensive days, I’ve split the work across at least 2 exercises because it can be hard to complete 7 heavy sets of a competition exercise without having to drop the weight, or without the form deteriorating considerably. Since this is a strength block and we want to be increasing specificity as we approach the competition, most of the exercises are either the competition lifts, or variations of them, with very few accessory exercises included. Mr McGainz is also a beginner and relatively weak (by powerlifter standards!), so I’ve included 2 sessions where he is doing the competition movement for Squat and Bench Press, as he would benefit from more specificity to learn technique. The variations I’ve selected are also ones aimed at developing technique.

Then, I’ve entered the set/rep schemes. Most of the volume is dedicated towards the most important movements - the competition exercises and their closest variations. The rep ranges are in the 3/4 - 6 zone - the range for developing strength. When I’ve wanted to keep the weight heavier, I’ve allowed for this with lower rep sets of 4, and when I want the weight to be lighter, I’ve given him higher reps of 6.

Then, I decide on the relative intensity to prescribe him. The percentages are a percentage of his most recent 1 rep max for that lift. Since he’s a beginner, I’ve avoided using RPE based intensity schemes, but this could be an option for your top sets if you feel that you can rate your RPEs accurately and honestly. The intensities for the competition lifts are within the rough strength phase guidelines of 75-90% for beginners, but on the lower end initially, as I want to start the block a bit lighter and easier, so he has some room to add weight to the bar as he progresses through the block. The intensities of the variations of the lifts have to be lower, as they are variations which make the lift harder - these intensities may be a bit more individual depending on where your strengths/weaknesses are.

Finally, I can finish this program template by adding in some general lat and back work. This wouldn’t be included in the MRVs for each of the 3 main lifts because these muscles are not prime movers during those lifts. It’s still helpful to have some lat and back training in your program however, as they are important for holding your position in the squat and deadlift. You could also add in some abs/light cardio at the end of some of the sessions if you wanted, but this is not essential.

Finally, I’d want to think about how to apply overload. Since this is a strength block, we’ll just progress the weights over time and keep the volume where it is for now. As a beginner, Mr. McGainz would probably do well on a simple, linear progression. I’d recommend adding weight slowly - just 2.5kg every week for the competition squat and deadlift, and maybe 2.5kg every other week for variations/accessories and for bench pressing. This can also depend on the absolute weight on the bar of course - 2.5kg is a much bigger percentage of 60kg than it is of 160kg. There are also clever ways to auto-regulate progression, for example by using RPEs, but I won’t go into those now.

Mr. McGainz could carry on like this all the time he feels he’s making progress, then deload and reset with a slightly different program after he feels fatigue is starting to build up (RPEs start to climb to above 9 or so). Or, as he’s a beginner with a competition in 16 weeks, we could pre-schedule in deload weeks after say, 5 weeks. He could then complete 2, 6-week strength mesocycles (starting 5-7.5kg heavier each time) and a short 4 week peaking block in time for his competition.

If this was the case, and if we assume Mr. McGainz’s previous 1RMs were: 140kg Squat, 90kg Bench and 180kg Deadlift, his finished strength mesocycle would look something like this:

The deload week should have only slightly reduced weight, but significantly reduced (by about 50%) volume. He should start his next strength mesocycle at about the same weights I used for his deload week - about 5kg below where he finished the first strength mesocycle. In the next block, you would also change up the variations and accessories slightly.

There are other ways you can play around with these same principles depending on what works for you, but this is just an example of how they could be applied. You could change up the loading schemes as well - instead of flat loading where all the sets for an exercise are at the same weight, you could have a heavier top set, then drop the weight (I like this method personally), or have a pyramid scheme loading pattern (yes, it is a scam).

You can see this program satisfies all the 7 principles of Strength Training quite nicely: He’s competition-style squatting, benching and deadlifting 1-2 times a week, and the variations used are close variations - so it satisfies specificity. The weight increases over time and the training is at a high enough intensity to produce strength adaptations - so it satisfies Overload. There is an appropriately timed deload at the end, so it satisfies Fatigue management. The frequency is about right for this lifter, with undulating session-to-session intensity, so it satisfies the Principle of SRA. There are variations of the main movements present, and these will change in the next block, so it satisfies Variation. These strength mesocycles will have been preceded by a hypertrophy block, and will be followed by a peaking block - so it satisfies the principle of Phase Potentiation. Finally, the overall volume, frequency, and exercise selection have been tailored to our lifter, so it satisfies the principle of Individual differences to at least some extent.

Conclusion

One warning I’d give you after absorbing all this complicated information is try not to overthink your programming. You can get a bit paralysed worrying about “am I hitting the exact right volume for my squats?” or “are my SRA cycles timed perfectly?”. At the end of the day, as long as you’re sleeping well, eating enough, training hard and not doing anything really stupid in your programming, you’ll make good progress. It doesn’t need to be exactly perfect first time. Jump right in and then start tweaking and experimenting and see what works best for you.

What all this hopefully will do however is just allow you to understand why certain things work and certain other things don’t, and also to tweak your program intelligently to suit yourself. While you shouldn’t overthink, what is worth doing is keeping track of your progress and noticing “oh, pin squats seem to really work for me” or “every time I move to 3 rep sets, I make the most progress” so you start to build up a picture of what you personally respond well to.

Hope this all helps!