Introduction

There is a useful tool produced by Juggernaut Training Systems which is detailed in the video above, for finding your Maximum Recoverable Volume (MRV). Your MRV is the maximum amount of volume (in sets per week) which you can feasibly recover from week to week. Therefore, you will generally want to keep below this volume. The only times you would want to intentionally exceed this volume is when you are planning to take a deload shortly after - a concept known as “functional over-reaching”.

Because MRV will vary depending on many variables, including gender, height, weight, strength, experience, sleep, diet, etc…, it can potentially be wildly different from one lifter to another. This tool simply gives you a rough, sensible indication to go off, based on where you score on these variables. It may not be 100% accurate, and if so you can adjust from this point up or down as you learn more about how your body responds to training. However, you are probably not the exception, and for most people, this will give them a very reasonable starting point.

Once you have worked out your MRV, you want most of your training to be around your Maximum Adaptable Volume (MAV) - the hypothetical volume at which you should make the fastest progress. This will be a range and should be just a few sets below your MRV. Especially if you’re in a hypertrophy block, you should be aiming to increase your volume over time to satisfy the principle of Overload. In this case, the way to apply this to your training is to: find your MRV, start a few sets below that at a manageable volume, then slowly increase the volume by half a set - a set each week until you hit your MRV and you feel fatigue starting to accumulate, then take a deload week.

Finding your MRV

To use this tool, first you start with a base range and adjust from there depending on how you score on all the variables detailed later. Keep in mind that there will be different base ranges for each of the 3 main lifts, as deadlifting will generate more fatigue than squatting, and squatting will generate more fatigue than benching. Therefore you can (and should) bench with a higher volume than you squat and squat with a higher volume than you deadlift.

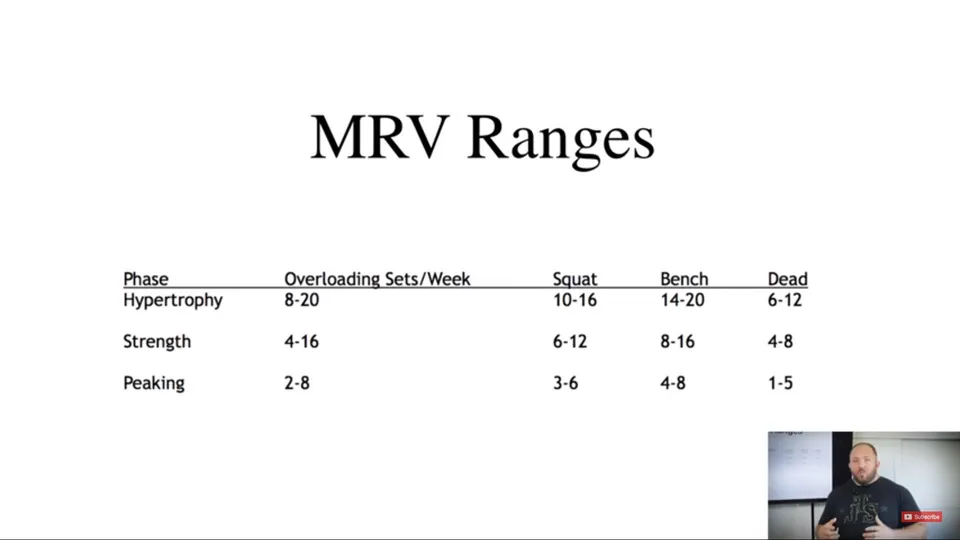

In addition, because different phases (Hypertrophy/Strength/Peaking) have different intensity ranges, there will also be a different base range depending on the phase you are in - as you will generate more fatigue during a higher intensity set, and so will be able to recover from less volume. The base ranges can be seen below:

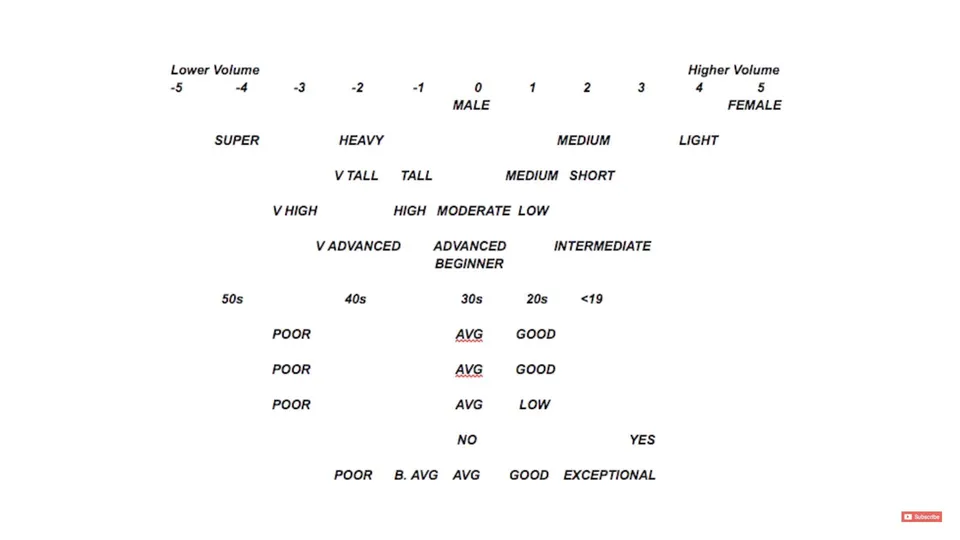

Now you have your base ranges for the different lifts, in the phase you’re in you can adjust these ranges to personalise it to you by seeing where you lie on the variables outlined in the picture below. How many sets/week you should add or take away is shown by where your answer aligns with the number line at the top. An explanation of how to answer the questions is given in the second picture.

It might be worth me going through a few of these variables briefly.

As you can see, females can tolerate significantly more volume than males (and slightly higher relative intensities for that matter). This is for 4 main reasons: 1) females (generally) are lifting less weight and so generating less fatigue per set, 2) females (generally) have less muscle mass on them than males, 3) females activate a lower percentage of their muscle motor units per rep than males, 4) males are fat and lazy and drink too much (kiddiiinngg).

Light people can generally tolerate more volume than heavy people - again, because they likely are lifting lighter weights and carry less muscle, so there is less muscle needed to repair.

Shorter people can tolerate slightly more volume than taller people - as they aren’t moving the bar as far each rep, and so each rep is generating less fatigue.

Weaker people can tolerate more volume than stronger people - as stronger people are lifting larger weights in absolute terms, which generates more fatigue. The strength classifications here are taken from the USPA’s lifter classification charts which you can download for Men here and Women here. The age categories are on the left and the weight classes are along the top (sorry, they have slightly different weight classes to us). If you’re a junior (19-23), which you probably are, scroll all the way down to “Junior”, and then scroll across to Total classifications for your weight category.

The relationship between experience and MRV is slightly more complex. A beginner can tolerate less volume than an intermediate lifter, as with some experience, you can increase your work capacity and your body’s ability to recover from training. However, as you become advanced and very advanced, your increased ability to recover doesn’t compensate for the increase in the weights you’re lifting, and you can’t tolerate as much volume.

Most of the other variables are relatively self explanatory. Note that while amazing sleep and diet doesn’t make a huge difference, poor sleep and diet really can give your recovery ability a big hit. As students, for most of us, our stress away from training is probably ‘medium’. We’re relatively active and stressed from work, but a lot of our time is spent sitting at a desk reading, which isn’t very physically stressful.

Historical recovery ability is a bit of a nebulous concept but it’s the best way they could try to account for your genetics/experience with your own body. This requires a little bit of soft intelligence. If you’ve built up a high physical work capacity from spending years being very active doing other sports, and you now find that you seem to be able to tolerate really intense work outs and still make progress, your Historical Recovery Ability is probably ‘good’ or ‘even exceptional’. If you’ve generally not been very active in your life and now when you go into the gym, even relatively small workouts make you sore for a week, you’re probably ‘below average’ or ‘poor’. You could also judge it by how sore/fatigued you seem to be after a particular size of workout. If in doubt, stick with average.

Example

So, to illustrate how to use this I’ll use an example. Let’s use an avatar lifter of “Mr. Broseph McGainz”. Mr. McGainz is a 20 year old, 80kg male of medium height. He’s been lifting for a year and after his first competition managed to put up a 410kg total (Class III Strength). His diet and sleep are average. He’s a well adjusted student without any serious problems going on in his life (apart from relentless bullying over his name), so his stress outside of training is probably medium. He’s not taking performance enhancing drugs, and his Historical Recovery Ability is average. He wants to design a program for a strength block.

Putting in these answers to our questionnaire, we find that we need to add about 7 sets to the base MRV ranges. Mr. McGainz comes out with MRV ranges of about: 13-19 sets in the Squat, 15-23 sets in the bench, and 11-15 sets in the deadlift, per week.

Keep in mind here, that “sets directed at a lift” includes not only the competition exercise, but also variations of that lift, and overloading accessories targeting muscles that are the prime movers of that lift (quads and glutes for Squat - chest, shoulders and triceps for bench - back and hamstrings for Deadlift). It does not include warm ups. Now, of course, a set of reverse hyper-extensions isn’t going to generate anywhere near the amount of fatigue as a heavy set of deadlifts. For this, you need to just use a bit of common sense. If almost all your volume if coming from heavy sets of the competition exercise, or even more fatiguing variations like wrapped squats or block pulls, then assume your MRVs are on the lower end of the above ranges. If most of your volume is coming from light accessories like leg extensions, reverse hypers and tricep kickbacks, maybe assume your MRVs are at the higher end of the above ranges.

Your “frequency” refers to how many times a week you practice one of the competition lifts, or one of their close variations. Unfortunately there is no perfect answer to the question of “how many times a week should I squat?” and one always has to give the classic coach cop-out answer: “it depends”. The optimal frequency will vary depending on the lifter, in a very similar way to Maximum Recoverable Volume (MRV).

Finding your Frequency

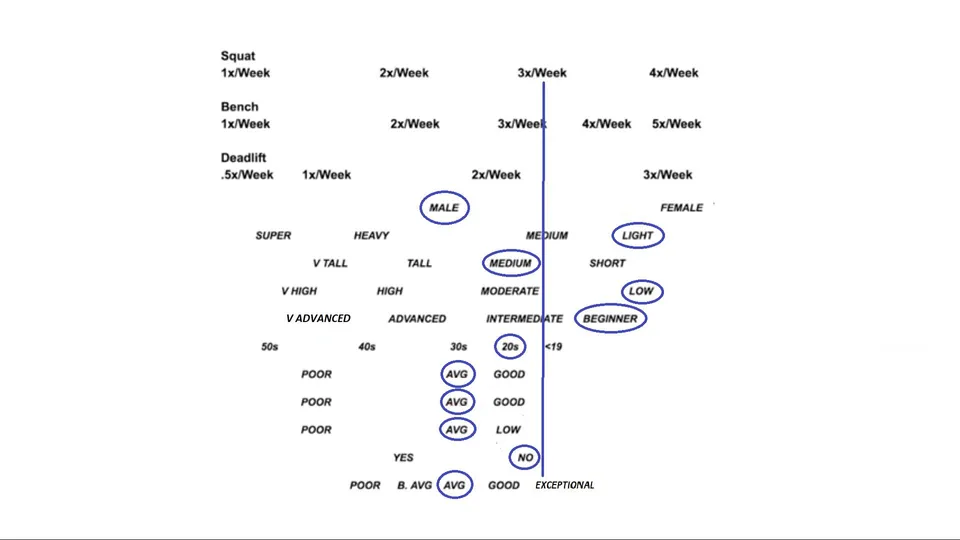

A rough starting guide for a frequency that should work for you can be found by answering the same questions used in finding your MRV. However, estimating your frequency from these is a little more… artistic. Essentially, Chad recommends drawing a rough trend line, averaging out the answers you’ve circled and seeing where that lines up with the scale along the top. So, for our example lifter Mr. Broseph McGainz from the ‘finding your MRV’ page, his chart would look like this:

So, for Mr. McGainz, we’d prescribe roughly 3 times a week squatting, 3-4 times a week benching, and about 2 times a week deadlifting. If he was a female but with the other variables the same, we’d maybe give her 3 times a week squatting, 4 times a week benching, and 2.5 times a week deadlifting.

Here, 2.5 times a week for deadlifting could mean either 2 times one week and 3 times the next, or 2 proper sessions a week, with one very small, light session with only some accessories that would count as only 0.5.

Again, these are only rough guidelines, but they provide a useful place to start if you don’t know where to begin, and they illustrate the principles and how different variables may affect your programming decisions. Feel free to start from this point, but then experiment with slightly altered frequencies and see how your body responds.

Also keep in mind that previous frequencies used in training may play a role. For example, if you’ve only ever benched 2 times a week in the past, and this chart tells you to bench 4 times a week, maybe spend a few weeks at 3 times a week first to allow your body to adapt to this more frequent stimulus, before moving up to 4 times a week.

Also remember, when doling out your total weeks volume across these frequencies, it can be a good idea to slightly undulate the sessions by intensity and volume. What this would look like is having one heavy session at the start of the week with more sets in, then a light session with fewer sets, then a moderate session. This allows you to really focus on that one heavy, high volume day, and relax a little on the other days and just practice your technique. You can also augment this with your exercise selection. For example, you might choose beltless tempo squats on the light day, belted pin squats on the moderate day, and competition style squats on the heavy day.