Introduction

Properly considering your recovery from training is often a forgotten piece of the puzzle. Many of us spend a long time focusing on our programming and technique, which we absolutely should, but fail to fully appreciate that what we do for the other 22 hours of the day will also have a huge impact on our results. Both are essential components - the training gives our body a stimulus, but our recovery determines how much gains we end up getting from that stimulus.

Of course, training is not totally devoid from our discussion on recovery. It is important to also structure our training in such a way that we can sustainably recover from it. This is discussed in the fatigue management section of the programming page, and includes tools such as rest days, deload weeks and active recovery phases of training.

However, if you are not recovering sufficiently from training in the long term, then ideally you should first consider the aspects discussed on this page - you may find that actually you can train that hard and make even more progress, so long as you get your sleep on point. Once you have optimised your recovery, then you can re-assess, and if you are still unable to recover, consider whether your training is simply outside of your Maximum Recoverable Volume (MRV) and needs to be reduced. If it is not possible for you to improve your recovery - for example, you’re in exam term and high stress is just unavoidable, then simply realise that this will have an impact on how much training you can realistically recover from, and adjust your training accordingly.

Note that this is a discussion on recovery from normal training. Recovery from injury is a different topic. Many of these strategies will also help you to recover from injury, but if you are injured, please, go see a doctor and/or a physical therapist for advice. The club offers discounted consultations with Piotr at Kelsey Kerridge at just £25.

If you’d rather watch than read, James Hoffman is a good source of information on recovery adaptive strategies, and I’ve linked a video of his below, but it doesn’t go into nearly as much detail as I do on this page. He does talk on this topic in more detail in several podcasts as well.

As with my other pages, the strategies below are ordered in terms of importance.

Things that Definitely Work

Sleep

Sleep is HUGE and by far and away the most important factor in your recovery. I cannot over-state how much more progress you will make if you get your sleep on point. Yet, unfortunately, it’s often neglected by busy Cambridge students who have too many coffee-fuelled late-night essays to write.

Sleep has a huge impact on your recovery from training, progress made from each session, power production, force production, motivation, technique and body composition. Just as an example that particularly stood out to me, there was a study conducted by Nedeltcheva et al. (2010) where they took 2 groups, both on a caloric deficit, but one sleeping 8.5 hours a night and one sleeping 5.5 hours a night. Both groups lost a similar amount of total weight over the 14 day period (about 3kg), but in the sleep restricted group, only 0.6kg of that weight was fat, and the other 2.4kg was lean body mass. In the well-slept group, they lost 1.4kg of fat and 1.5kg of lean body mass. The sleep restricted group also experienced more hunger. These subjects were not resistance trained, so of course these numbers would look more favourable in both groups if they were, but still, the difference is staggering - if you went on a cut and only 20% of the weight you lost was fat, that would be atrocious!

And of course, sleep has a huge impact on how much you can focus, how productively you can study and how much information you can retain - so even if you’re working hard revising in exam term, you should still be getting enough sleep! It also improves your mood and will probably just improve your life in general.

So, how exactly do we improve our sleep? Well, we can consider the total amount of sleep, when that sleep occurs and the quality of that sleep.

Total amount of sleep

The recommendation here is simple and you probably all know it - try to get at least 8 hours of sleep a night. 9 or 10 is even better. Beyond 10 you probably don’t get much extra benefit. Don’t go below 7 hours a night if you can help it. The more advanced a lifter you are, the more you should be aiming for the higher end of these recommendations. A good rule of thumb is that if you NEED an alarm to get yourself up on time in the morning, you’re probably not sleeping enough as your body should be able to naturally wake up at that time.

I know some people say they can function fine on 6 hours a night and just don’t need as much sleep. This is almost certainly not the case for you. What commonly happens is that people just get used to being under-slept, without realising how much worse their day-to-day functioning is. In a study looking at adolescents over a 5 day period of sleep restriction, their subjective sense of sleepiness increased after the first night, but then remained about the same, while their actual performance in reaction time tasks continued to worsen over the next 4 days (Jiang et al., 2011). This indicates that our subjective sense of sleepiness is not accurate at assessing our objective functioning when we are chronically under-slept. So no, you’re probably not that one person in a million who can genuinely get by just as well on 6 hours of sleep a night - you just don’t realise how well you could be functioning if you slept more!

Sleep timing & regularity

Our bodies work on a circadian rhythm. In terms of sleep, this is mainly regulated by a hormone called melatonin. Melatonin levels are dictated by exposure to blue wavelengths of light and increases in the evening and is highest at night. Essentially, it makes you sleepy. What naturally follows from this of course is that sleep quality will be highest at night.

This sounds obvious, but of course consider that if you are someone who tends to go to bed late (e.g: 1am) and then get up late (e.g: 9am), you might be getting 8 hours of sleep, but the quality of this sleep would be higher if you shifted it earlier so you are going to sleep at about 10pm and waking up at 6am.

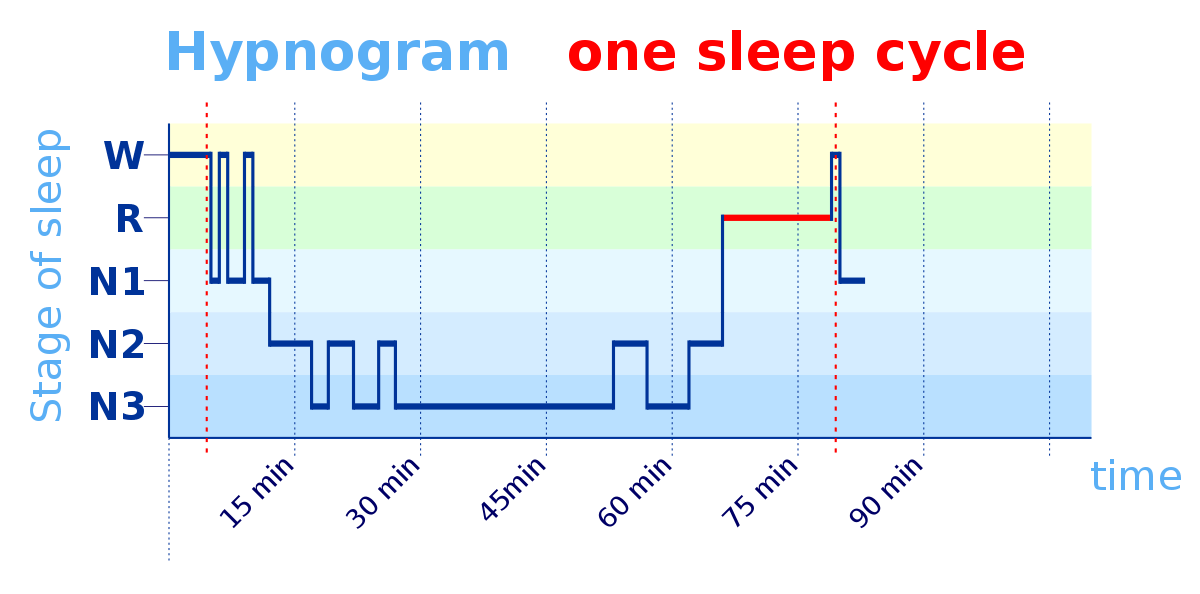

When sleeping, your body goes through sleep cycles - where it descends from light sleep, to deep sleep, back up to light the REM sleep. One of these cycles lasts approximately 90 minutes. You will feel the most well rested if you wake up at the end of one of these cycles, from a light sleep phase, rather than waking up during deep sleep. This means that the amount you sleep should ideally be in multiples of 90 minutes. This is another reason why waking up to an alarm can be a disadvantage - you run the risk of it waking you up during a deep sleep phase, while if you wake up naturally you will always wake up at the end of a sleep cycle. There are sleep-cycle alarm apps you can get which claim to detect how much movement you make in order to estimate what stage of sleep you are in. They then go off when you are in a lighter sleep stage.

Naps are an interesting one - ideally you should probably aim to get enough sleep at night and then not require naps during the day. However, if you have a poor night of sleep, can you compensate for it by having a nap during the day? Potentially. Naps certainly can be beneficial, for the right length at the right time. A short power nap of about 20 minutes does acutely improve focus and concentration afterwards, but probably won’t do anything to get you out of your sleep debt. If you have a longer nap, you should try to make it a full 90 minute nap, so that you go through a full sleep cycle. You should avoid napping after about 3-4pm so that it does not interfere with your ability to sleep the next night.

Finally I’ll mention sleep regularity. This is actually a really important one. You should try to consistently aim to go to bed and wake up at the same times every day. The most common pitfall here is that people go to bed at a consistent time during the week, then sleep in at weekends and go to bed later. I know it’s hard but please try to avoid this. Also, if you do get to sleep unusually late one night, it might be better in the grand scheme of things to still wake up at your normal time, so that you can then go to bed early the next night and not disrupt your sleep cycle.

Sleep quality & sleep hygiene

The term “sleep hygiene” refers to practices you can do in order to improve the quality of your sleep. There are as follows:

- Avoid screens before bed - this is a hard one to do in the modern age, but if you can at all avoid your TV/laptop/mobile phone for about an hour before you go to bed, this will make a massive difference to your sleep quality. Those blue wavelengths of light disrupt your melatonin production and keep you up for much longer. You can remove the blue wavelengths of light from your laptop and phone after a certain time in the evening, which helps, but it’s probably still best to avoid them altogether if you can.

- Get an eye-mask - Blocking out light from reaching your eyes with an eye-mask will improve the quality of your sleep, since that light can disrupt melatonin levels even at night and in the morning, especially if your curtains aren’t very good. Some people recommend black-out blinds, but I think an eye-mask is a much cheaper way to get the same effect.

- Have a bedtime routine - Doing something routine that relaxes you in the 20 minutes before bed every night will help to get you in a good state for sleep. This could be reading a book, doing some meditation, listening to a podcast… whatever works best for you.

- Cool down your room - Your body temperature drops at night. Subsequently, if your room is just a touch cooler than regular room temperature at night, the quality of your sleep is improved slightly. Buying a small desk fan for the summer can be really helpful here.

- Improve your bed/pillows - This might be too expensive for some of us to manage, and probably matters the least, but if you can get a nice comfy pillow, and maybe buy a memory foam mattress topper, that’s going to improve the quality of your sleep.

- Avoid caffeine/alcohol/nicotine before bed - All of these will decrease the quality of your sleep. Caffeine is probably the most common sin here - caffeine has a long ~6 hour half life, so try to reduce your total caffeine intake and avoid caffeine after about 4pm latest. As mentioned in the nutrition page, an L-theanine supplement may partially reduce caffeine-related sleep disturbance and can be used if you absolutely have to have caffeine later in the day.

Diet

Diet is discussed in far more detail on the nutrition page, so it will suffice to say here that if you are in a calorie excess, particularly if your carbohydrate intake is higher, your recovery from training will be vastly improved. If you are dieting and your calories are lower, you should try to maintain your carbohydrate intake as much as you can and do carb cycling so your carbs are higher on hard training days. However, it’s an unavoidable fact that your recovery will take a hit during a cut, so take this into account in your training.

Relaxation

Relaxation is something that’s often forgotten by people when they think of recovery strategies. They always think of things they should do, whereas actually a lot of it can come down to things you should do less of. Try to set aside at least an hour or two a day where you just chill. Lie down, play video games, read a book - whatever relaxes you and de-stresses you. And again, if your job or circumstances dictate that you can’t have much relaxation time, take this into account in your training - but to be honest, if you can at all get it in, it will probably benefit you in many aspects of your life.

There are some olympic athletes, for example Meso Hassouna, the 96kg olympic weightlifter who will literally spend almost every hour he is not training lying down in bed, just chilling out. His family will bring him all his meals so he doesn’t need to get up. I heard a story were he was legitimately concerned for the safety of his friend and fellow weightlifter, Ilya Ilyin, when he was going out to the cinema. Meso was convinced that 2 hours of sitting upright would impede Ilya’s recovery on the lead up to his competition. Now, I’m not saying this is the level we should be aiming for! Meso is a full time olympic athlete. However, this story did hammer home to me the extent that some athletes will go to just to relax, and how they view that as a crucial step to their success.

Stress Management

Probably good general advice for most Cambridge students, managing both physical and psychological stressors can actually make a big impact on your athletic performance. This overlaps greatly with relaxation.

Managing stress is a skill that can be learnt. If you can continually decrease the amount of emotional arousal you experience to stressors that affect you throughout your day, you’ll expend less energy worrying about it and have more energy left over for your recovery. Also, your mood and general life will improve. A good tool for learning this skill can be mindfulness. I would recommend the Headspace app, and 10 minutes of meditation a day, to anyone, not just those who struggle with mental health issues. We could all do with building this skill of being more mindful and aware of our emotions and anxieties.

Again, an implication of this is that you may need to adjust your training during times of high stress - during exams, if your partner breaks up with you, if you’ve just moved house - maybe preemptively reduce the volume in your training just a bit.

Things that might work, and should be reserved for select situations

Here is where we discuss more of our ‘active’ recovery modalities.

Ice and Anti-Inflammatories

Holding an ice pack over your muscles for 20 minutes or so, or using an anti-inflammatory cream (usually a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen), can be an effective way to acutely increase the recovery of your muscles in that local area. However, they come with the caveat that they probably also slightly decrease the gains you ultimately would have made. Essentially, by training you damage your muscles and cause inflammation, and this is why they feel sore afterwards. By dampening down that inflammation, you do decrease the recovery time. However, the inflammation itself is probably one of the things that signals to your body to produce more muscle in order to adapt.

Therefore, you wouldn’t want to use these strategies after every session. However, they can have uses in specific circumstances. They can certainly help to work around the pain of an injury in a specific area (if you should still be working around the pain! - again, see a physical therapist). Also, if you absolutely need to perform on a certain day (for example, you have a competition tomorrow), but you haven’t tapered very well and you still feel sore, they might help to slightly reduce your fatigue going into the competition.

Compression

by compression, there’s a couple of things I could mean. Firstly, there’s proper compression devices such as Normatec leg recovery systems. For these, essentially the same advice applies as to ice and anti-inflammatories - they will help recovery but they will also shave off some of your gains.

There’s also compression leggings, like skins, or compression stockings. These add just a little bit of pressure and are designed to improve the blood flow in your legs. They probably don’t make much difference for a young healthy person most of the time, but I have noticed that they can really help if you are going on a long journey in a car or plane, to help mitigate the negative effect that the travel has on your recovery.

E-Stim

E-stim is an electrical muscle stimulator. By keeping some low level activity going in the muscle, it aims to improve recovery. Most of the literature around E-stim revolves around recovery from injury, where it shows some promising results. However, in terms of recovery from training, the improvements seem to be very small. It’s certainly no where near as effective as just taking a light training session to get some blood into the muscle and improve recovery.

Massage

A lot of high level athletes will get very regular massages. They tend to love them and self report a lot of benefit. Quite a few researchers have looked into this to try and find a physiological mechanism for massages to improve muscle recovery… and have some up short. It’s probably the case that massages don’t so much have any special, unique mechanism in muscle recovery, but instead are just really good at relaxing people and reducing the tension they’re holding in their muscles, which then has an indirect positive effect on muscle recovery.

I’ll briefly discuss foam rolling here as well. Again, there’s no evidence that foam rolling really does anything to change the muscle structure and reduce fatigue. However, it is true that after foam rolling a sore area, it feel significantly less sore when you exercise immediately after. The effect here is probably one of perception - meaning that it has a short term effect of reducing your perception of pain in that sore muscle. This can be useful to use in a warm up, but bear in mind that you probably only need ~5 minutes of foam rolling a particularly sore area, and the effect probably only lasts for 15 minutes or so afterwards.

Things to avoid too much of

This section is here to bust some myths on things that people might think benefit recovery, but actually either have no effect, or may even have a negative effect if you do it too much.

Stretching

This is one that catches a lot of people out. Everyone talks about stretching as though it improves muscle recovery. Now don’t get me wrong, ensuring that you have the pre-requisite mobility to do the powerlifting movements with good technique is an important component of success in the sport. However, doing stretching purely for the purposes of recovery is probably not a good idea. At the end of the day, it’s actually another stressor that you’re adding to that muscle, and so is probably going to add fatigue if you do it too much, rather than take fatigue away.

Cardio

A lot of people will think that doing some cardio will help their recovery by getting some blood into the muscles, but if you do too much of it, again, you’re adding fatigue rather than taking fatigue away. Cardio is also a stressor to the system. It uses energy and so therefore it adds fatigue. If you want to get some blood flow into the muscle to improve recovery, a light training session is much more effective and also allows you to practice some technique work. Of course, if you’re doing cardio just because you want to be fit, or you enjoy it, or it’s necessary for another sport you’re doing, that’s fine - but don’t do it because you think it will improve your recovery.

Heat

Heat can be beneficial in small doses - for example if you use hot & cold therapy on a sore muscle with 20 minutes of heat, and 20 minutes of an ice pack. However, going into a sauna for an hour is not going to help your recovery. You’re essentially subjecting yourself to heat stress - so again, it will add fatigue rather than take fatigue away. Add on top of that the fact that it will dehydrate you and you definitely don’t have an effective recovery modality.

I hope this helped guys! Now close your laptop and go to bed.

References

- Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Penev PD. Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. 2010:14.

- Jiang F, VanDyke RD, Zhang J, Li F, Gozal D, Shen X. Effect of chronic sleep restriction on sleepiness and working memory in adolescents and young adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33(8):892-900. doi:10.1080/13803395.2011.570252